Introduction

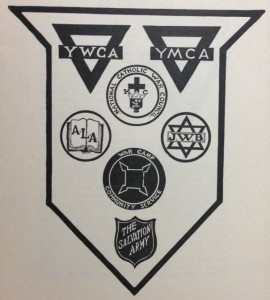

The two UWWC organizations that represented American Catholics were the Knights of Columbus and the National Catholic War Council. Though both eager, as most Catholic overall were, to prove the loyalty and patriotism of Catholics through war work the two were quite different in origin, composition, and private goals. The clashes between the two, which both put aside for the sake of a united Catholic front in the Campaign, are illustrative of one of the major divisions in Catholicism of the time: between the hierarchy (i.e. ordained priests and bishops, represented by the Council) and the laity (i.e. all other Catholics, including the K of C). The struggle for dominance between the two resulted in the Knights submitting to the Council’s authority, but with the acknowledgement that the Knights were the de facto force and presence of Catholics in the training camps. This compromise can be seen in the relatively equal status given to both in their joint icon (see the upper-middle symbol).

The Knights of Columbus

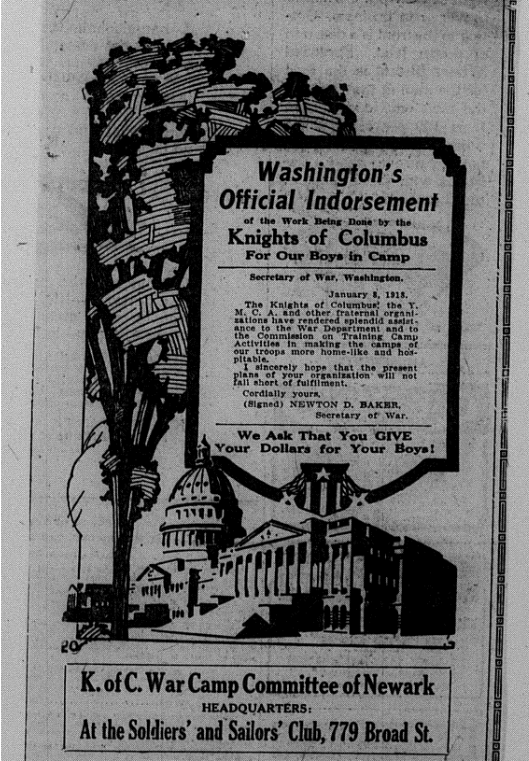

Before even the formation of the National Catholic War Council the Knights of Columbus were active in their support for the American war effort. By April 17, 1917, just eleven days after the formal declaration of war, the Knights wrote to President Wilson pledging the 400,000 member order’s “determination to protect [the nation’s] honor and its ideal of humanity and right.”[1]

Founded in 1882, the Knights’ goals included providing a respectable society for American (primarily Irish) Catholics and countering accusations that American Catholics were disloyal to the nation and plotting with the Papacy to undermine the government. The chosen patron of the order was also aimed at creating a reputation of “Americanism” – Columbus’ role in American history was an implicit claim for the important positive influence of Catholics in American life.[2]

During this era Catholics was often the target of various attacks and accusations of immorality, treason, or being un-American. This pattern persisted during the United War Work Campaign, when, for example, a newspaper article (“War Chest” Unmasked) accused the Knights of stealing money from the YMCA and Red Cross in order to fund its activities on behalf of “the papal government, which is the most autocratic in the world.”

The Knights combated such rumors in various ways: in 1900 the first members of a new degree, patriotism, were created, and in 1914 the Knights created the “Committee on religious prejudices,” intended to directly address rumors and misconceptions about Catholicism. It was headed by Kentucky businessman Patrick Henry Callahan, who would go on to serve in the Knight’s war drive and the UWWC.[3]

The Knights also served as a kind of guardian for Catholic men and youth. Citing examples of the French government curbing parochial education, the Knights, as the ‘flower of Catholic manhood’ took on the protection of religious education for American Catholics. They were also seen as the Catholic answer to the YMCA, the Protestant youth organization that often succeeded in attracting Catholic youth. The Knights’ council house movement was an attempt to “stop the leakage” of youth Catholic men to non- or anti-Catholic organizations like the YMCA.[4]

This rivalry with the YMCA would continue after America’s declaration of war and into the United War Work Campaign. Both organizations had experience with army camp recreation from their assistance on the Mexican border in 1916, but Wilson, being a highly religious Protestant, and also a personal friend of Y director Dr. John Mott, initially favored the YMCA. In late April of 1917 Wilson issued Executive Order No. 57, in which he urged officers to cooperate with the YMCA in any ways possible in that organization’s war camp efforts. The Knight’s request for a similar presence in camps was instead forwarded to Raymond Fosdick, who gave his approval (dated June 19) for the Knight’s presence in military camps.[5]

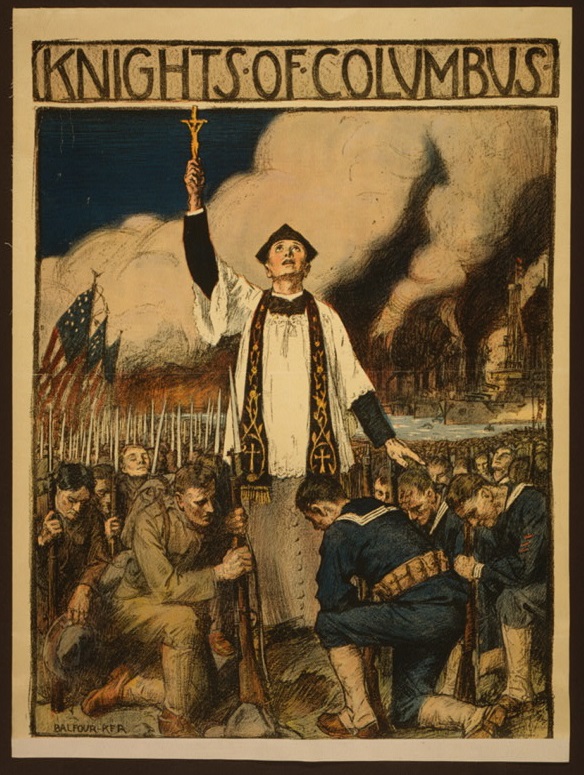

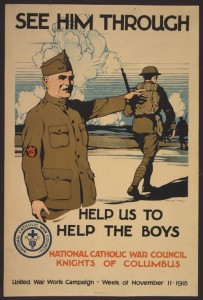

By September 1917 the Knights were already positioning themselves as the official representatives of the Catholic war effort in American military camps. In one of their campaign pamphlets they describe the organization as “keep[ing] our four hundred thousand Catholic soldiers and sailors clean in soul and body, and steadfast in the Faith of their Fathers” while at the same time creating “amusement and recreation for all our soldiers, regardless of creed.” These were the dual goals of the Knight’s activities: play the role of supporter and defender of the faith in America (especially to prevent a war camp monopoly by the YMCA), in the form of Catholic chaplains and Masses in the camps, while furthering the cause of Catholicism as a respectable “American” institution by serving the nation as a whole. This method of advancing Catholicism was advocated by P.H. Callahan, who said that “The War will kill bigotry….[i.e.] the jealousies, enmities, bitterness and hate, wholesale inventions of scandal, studied falsehoods, agitated feelings of anxiety, fear and suspicion born of dark thoughts and evil rumors.”[6] While this would not entirely be the case, it was a competent strategy for Catholicism at the time.[7]

In justifying why the Knights, a lay fraternal organization, should represent the Church’s war effort, the reasoning was the “There was need for some National Catholic lay body to take up this great work,” and that the Knights were best suited to this work because of their experience and reputation from their Mexican border work.[8]

National Catholic War Council

The other Catholic organization in the campaign was the National Catholic War Council. Father John Burke and Cardinal Gibbons organized the Catholic hierarchy (i.e. the bishops of the church) to form the War Council in response to America’s entering the war, and therefore had to catch up to the Knights in terms of functionality and efficiency. The Council quickly tried to assert its authority over the Knights, but the Knights’ already widespread presence in the camps forced a compromise between the groups. Nevertheless this was part of a trend of the hierarchy asserting dominance, on the national level, over a lay organization: a trend that would continue as the church ‘nationalized’ itself.[9]

The initial idea for a national council specifically in response to the war came from Fr. John Burke, a Paulist priest and editor of the Catholic World. Burke was already an advocate of both the hierarchy and the organization of the church along national, rather than ethnic, lines. He had already formulated several nationally organized bodies before the war.[10]

Burke presented his plans for a national organization, under the hierarchy’s supervision, to Cardinal Gibbons in the summer of 1917. Gibbon’s gave his approval when other high-ranking clergymen agreed, and a meeting was called on August 11 at Catholic University of America. It was there that the council was formed.[11]

The relationship between Burke and Gibbon’s is representative of the War Council’s overall composition – high-ranking and prominent clergy gave their approval for actions and served as symbolic heads and representatives, while the lower clergy and laity carried out the day-to-day functions of the organization. Gibbons lead the former and Burke the latter.[12]

During the campaign the War Council’s focused on organizing and coordinating diocesan war efforts. They acted as a centralized body that could communicate at the national level with the government, and prevented duplicated efforts and overlapping by the dioceses.[13] This focus resulted in the Council lower profile in campaign literature compared to the Knights, whose representatives (affectionately dubbed “Casey” by the troops) were actually in the camps and overseas.[14]

By the campaign and war’s end Catholics, and in particular the Knights, had emerged in a much better position than they had started. Catholics had proved their loyalty and patriotism to America, although this would soon be overshadowed by the nativist sentiment of the 1920’s. Meanwhile the Knights grew in status and recognition, with “Casey” having won much love from American troops overseas; they had played their dual role well, as a “regular guy who never pushed his religion” to the military at large but a coreligionist and comfort to Catholics. Finally he War Council proved so useful to the Church that in September 1919, when the organization was supposed to end, it was instead decided to continue the organization in peacetime as the National Catholic Welfare Council.[15]

John J Burke, C.S.P.

Rev. John Burke was one of the primary forces behind the creation of the National Catholic War Council in 1917. An advocate of the Catholic church’s hierarchy (i.e. its ranked clergy), he promoted national cooperation and organization for the war effort, under their direction, in the form of the council. This reinforced the power and authority of the clergy, particularly vis-à-vis lay organizations such as the Knights of Columbus.

Burke’s life would be defined by the religious order he joined in 1896, at the age of 21. The Paulist Fathers, founded in New York in 1858, were a missionary society that specialized in mass communication. Burke took part in this, helping to found both the Paulist Press and the Catholic Press Association. In 1903 he joined the staff of Catholic World, a Paulist newspaper, and remained there for the rest of his life as an editor.[16]

When the U.S. entered World War I, Burke took a highly active role in organizing Catholic support efforts. He both founded the Chaplain’s Aid Association, which supplied the army with Catholic chaplains, and was on of the founders of the National Catholic War Council. His letter to Cardinal Gibbons, which urged a meeting of all Catholic aid societies for the creation of a cooperative organization, that led to the creation of the National Catholic War Council. Burke himself was chairman at the first meeting of the Council, and said of their forthcoming efforts that “the most glorious pages of [the Church’s] history in this land are about to be written.”[17]

During the war Burke would serve as chairman of the Committee on Special War Activities (which was essentially in charge of all non-Knights of Columbus work of the Council) while continuing his involvement with the Chaplains’ Aid Association (now under the umbrella of the War Council). He also served in an ecumenical group called the Committee of Six, a body of Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish representatives on morality to the War Department. For all of these services Burke would receive the Distinguished Service Medal in 1919.[18]

James Cardinal Gibbons

Gibbons was an influential and well-respected representative of the American Catholicism of his time, even outside of the Church. Although his participation in the United War Work Campaign was primarily symbolic and His leadership in the National Catholic War Council granted it legitimacy in the eyes of both Catholics and non-Catholics, and its goals fit well-within his range of civic and Catholic advocacy. A staunch promoter of American Catholicism, as opposed to ethnic, his views dominated the Catholic campaign in the downplaying of ethnic identity and loyalty in favor of “Americanism”

Gibbons impact on Catholicism in America reached far beyond the campaign, however. Born in Baltimore in 1834, Gibbons had a near lifetime of service to the church behind him at the time of World War I, first as Bishop of Richmond and, from 1877 until his death in 1921, Archbishop of Baltimore. He was appointed cardinal, a highly influential and prestigious position within the Catholic Church, in 1886; it was from just such a position that he could exercise influence over his coreligionists.[19]

Gibbon’s bears superficial similarities to the progressives of his days, inasmuch as they focused on the same social ills: public education, political corruption, and the condition of the lower classes. Gibbon’s approached these from a Catholic theological perspective, however, and his reasoning and conclusions were always rooted in such a worldview. The most prominent cause he championed was organized labor. The Catholic Church had been, as an institution, long suspicious of this; it tended to view unions simply has hotbeds of radicalism and socialism, both of which were usually hostile toward the Church. Gibbon’s grounded his defense in Catholic principles and teachings (concern for the poor, the naturalness of community, and the need to reach out to the unfortunate to maintain the unity of the Church). [20]

[1]Christopher J Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism: A History of the Knights of Columbus 1882-1982 (New York: Harper & Row, 1982), 190.

[2]Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, xi-xii, 5; Thomas J Rowland, “Irish-American Catholics and the Quest for Respectability in the Coming of the Great War, 1900-1917.” Journal of American Ethnic History 15, no. 2 (January, 1996): 9.

[3]Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, 138-139, 154.

[4]Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, 175-176, 160-161.

[5]Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, 193; The Wilson Papers, Reel 250, Case File 286

[6]Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, 189.

[7]Wilson Papers, Reel 250, Case File 286; Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, 197.

[8]Wilson Papers, Reel 250, Case File 286

[9]Chester Gillis, Roman Catholicism in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 69.

[10]Henry Ward Bowden, Dictionary of American Religious Biography (Westport, CT: Greenwood press, 1993), 81; Joseph H. Piper, Jr. American Churches in World War I (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1985), 26.

[11]Michael Williams, American Catholics in the War: National War Council, 1917-1921 (New York: Macmillan, 1921), 106; Piper, American Churches in World War I, 27-28.

[12]Piper, American Churches in World War I, 70, 92, 93.

[13]Williams, American Catholics in the War, 92.

[14]Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, 227.

[15]Lynn Dumenil, “The Tribal Twenties: ‘Assimiliated’ Catholics’ Reponse to Anti-Catholicism in the 1920’s. Journal of American Ethnic History 11, No. 1 (Fall 1991): 23; Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, 227; Piper, American Churches in World War I, 85.

[16]William John Shepherd, “Americanizing the Church: John J. Burke.” The Catholic Historical Society of Washington 25 (Winter 2014): 31-32; Henry Ward Bowden, Dictionary of American Religious Biography (Westport, CT: Greenwood press, 1993), 81.

[17]Shepherd, “Americanizing the Church,” 32; Michael Williams, American Catholics in the War: National War Council, 1917-1921 (New York: Macmillan, 1921), 106, 117.

[18]Shepherd, “Americanizing the Church,” 32; John. J. Burke, “Catholic Activities in War Service” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 79, (Sep. 1918), 217.

[19]Henry Ward Bowden, Dictionary of American Religious Biography (Westport, CT: Greenwood press, 1993), 201-202.

[20]Bowden, Religious Biography, 202; Edwin Gaustad and Leigh Schmidt, The Religious History of America (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2002), 241-242.